1)

Why I’ve been trying to create a culture of failure in my classroom

2)

What’s a ‘pre-mortem’ and how could it help improve teacher-effectiveness?

1) Embracing failure at the student level

During an interview with Thomas Edison before his successful invention of the light bulb he said: “I have not failed 10,000 times. I have not failed once. I have succeeded in proving that those 10,000 ways will not work. When I have eliminated the ways that will not work, I will find the way that will work.”

I’ve had my new classes for a couple

of weeks now and all of them are able to finish off some of my sentences. This

has in the past disconcerted me. In China after a term two of the boys at the

back of one of my classes gained the confidence to interrupt me, as I was about

to start an activity. “Ok, let’s go for it!” Tony and Never (they chose their

own Western names) chorused before I could get the words out. I left the lesson

trying to convince myself “I don’t say that all the time?” In Spain my students

always seemed to walk between lessons painfully slowly in the heat of the

midday sun. I soon began to overhear what sounded like “Mr Hurry up”. In France

it was the other way round - it was me always getting caught slightly off-guard

by the calls of my primary school children whenever I got out my ‘Excellent

effort’ stamps. “Tampon, tampon” they used to call (tampon being the French

word for rubber stamp.) In Uganda it was “Ok, let’s sing” – our students were always

ready to stand up and sing; even when it was an increasingly lyrically-challenged

attempt to shoehorn Maths into simple tunes such as ‘Frère Jacques, Frère Jacques’

which became ‘mean is average, mean is average’ (complete with hand gestures).

However I’ve started to try and

embrace my apparent verbal predictability. “What don’t I mind?” I’ll ask before

starting an activity, “if we make mistakes” will come back the response. “What

do I want to see?” “Evidence of effort” the students reply.

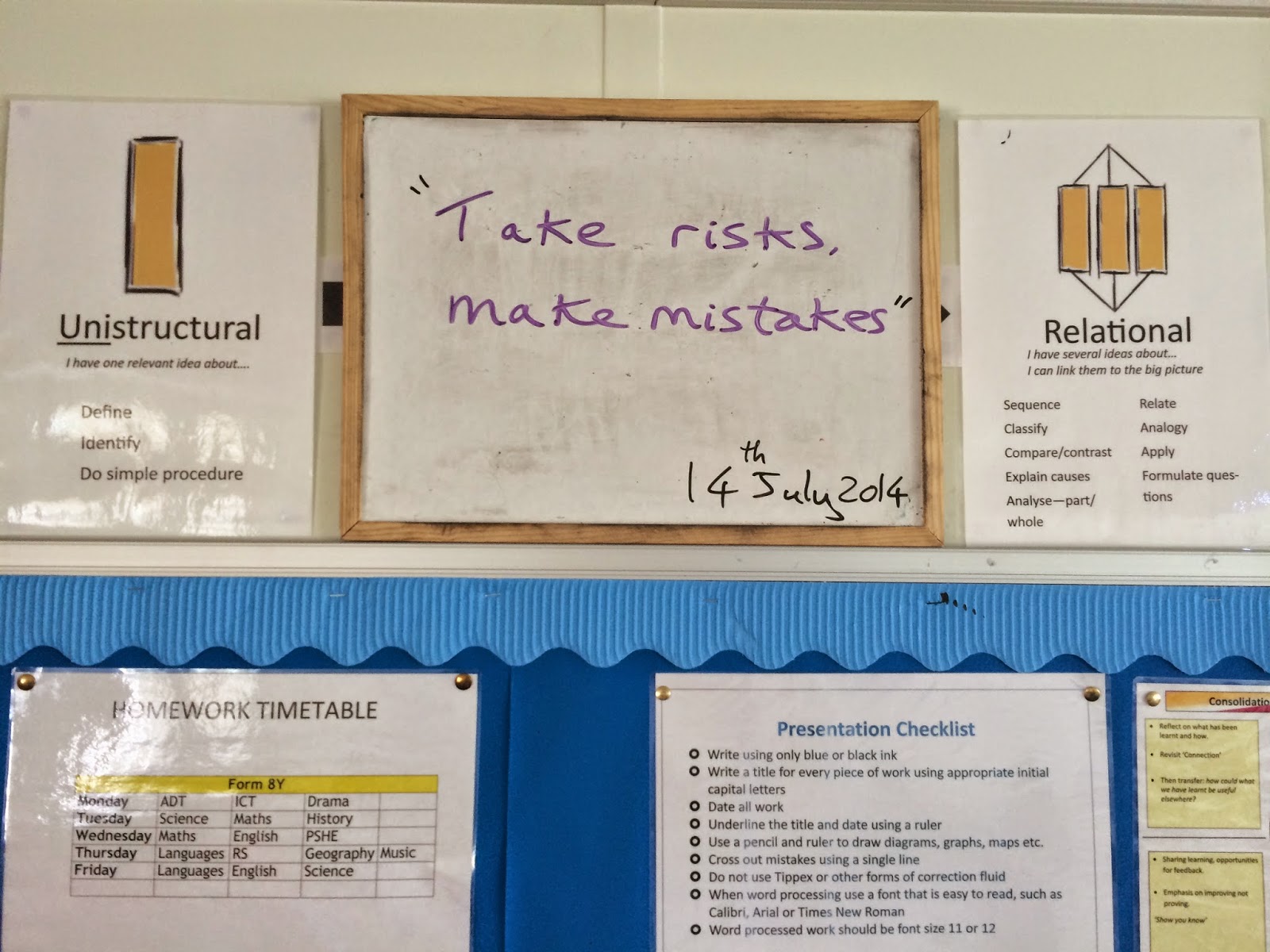

To reinforce this I occasionally refer

to the ‘quote of the week’ board (see pic. above) on the wall at the front of

my classroom that invariably has a quote along the lines of “take risks, make

mistakes’ – anon. “You only regret the things you don’t do” – anon. “Success

always starts with failure” – anon. “A person who never made a mistake never

tried anything new” – Einstein.

I also regularly use mini-WBs in my

lessons, not simply because they are a fantastic, quick AfL tool but because

students are often uneasy about making lots of mistakes in their own books.

Using mini-WBs removes this anxiety, as they know there’ll be no permanent

record of their failures. Sure enough, over recent lessons I have started to

see fewer and fewer empty whiteboards being held up.

I have no evidence to show that my

students use mini-WBs a lot in my lessons. However, my department does spend a

surprising amount on student whiteboard pens.

I’m always curious to learn how ideas

translate across subjects. It was great to read LearningSpy’s blog on marking, where he discussed

encouraging students to think of writing as drafting: “I have started referring

to writing as ‘drafting’, as in: ‘I want you to draft an article on…’ This then

encourages re-drafting.”

“I can accept failure, everyone fails at something. But I can't accept

not trying.” - Michael Jordan.

To reinforce this classroom culture I only reward effort (see pic.

below) and I start/end each lesson by getting students to write down one Maths-related

success and one target from their lesson.

2) The Pre-mortem – embracing failure at the staff level

It’s very nearly the end of another academic year and so I’m sure like

many teachers, aside from occasionally daydreaming about the summer holidays we

will be involved in completing school/departmental improvement plans and writing

performance appraisal targets for next year. There is still much uncertainty

and discussion surrounding the topic of performance-related pay but it is clear

that the ritual of meeting for performance appraisal whereby staff set their

targets with renewed enthusiasm at the beginning of each year and are reminded

with a wry smile at the end of the year what their targets were, may be far

less care-free in the near future. I have often questioned the effectiveness of

such meetings, however once the year has started there always seems to be more

pressing things to do than log on to a performance management system and ‘upload

evidence’.

I’m always wary of well-meaning attempts to ‘reinvent the wheel’ and am

far more comfortable discussing what teaching may be able to learn/adapt from other

industries. It was with this in mind that I pitched the idea of the ‘pre-mortem’ to my head of department.

“While many

institutions conduct a post-mortem to examine why a given project has failed,

Klein walks us through an exercise that can spot potential failures before

things have gone wrong.”

Why a pre-mortem?

When we ask close colleagues for feedback they often

avoid the negative. People are usually way too over confident at the beginning

of a new project. The pre-mortem aims to temper this. A ‘pre-mortem’ is a technique

aimed at freeing people who might otherwise feel that they may not look like a

‘team player’.

“During a ‘pre-mortem’ the demand characteristic becomes: show me how smart/experienced/clever you are by identifying things that we need to worry about.

During a postmortem - everyone benefits from the

knowledge gained via the process except the patient (they're dead).”

The aim is to run through the process to find out what might go wrong before it goes wrong/the patient (project/product) dies.

Example dialogue

“We're 3

months into the 6 months. It's obvious the project has failed.

There's no doubt about it. It

can't succeed. 6 months later we don't want to talk about it. We don't even

make eye contact. It's that painful.”

“Now, for the next 2 minutes.

I want each of you to write down why this project had failed. We know it

failed. No doubt about it. Write down all the reasons.”

Evidence

•

“1 item from each person's list -

given to a catalogue of all the ways the project might fail.

•

Now go round the room and each

give one way/thing you could do to help the project/hadn't thought of before to

try to make it more successful.”

I am, for the first time genuinely

excited as we get together this week to complete our departmental improvement

for us to be asked in advance to use our talents and experience to discuss why

a project may fail and more importantly what we could do to ensure it doesn’t.

I’ll write a comment below the blog at the end of the week to let you know

how we get on.

For

anyone interested in reading about the research behind well-known success

stories:

Bounce: The Myth of Talent and the Power of Practice -

Matthew Syed

Outliers: The Story of Success - Malcolm Gladwell

Mindset: The New Psychology of Success - Carol Dweck